My new heart doesn’t really belong to me. And neither does my old one.

The second doctors removed my original, it seemed, all rights to it were void. It’s as if it no longer had my history, my DNA, me at its foundation. Fortunately, I had a friend, quick on her feet, who suggested I give my heart to the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia. Days before the surgery, I signed the paperwork. The decision was done.

Probably subconsciously I was happy to know my heart might be returning to the state where I was born and raised. More importantly, though, I felt satisfied that I knew where, exactly, my heart would go once it was lifted from my chest and more or less what would happen to it.

Months after my transplant, knowing my heart was safely shipped to Philly, I asked one of my heart doctors what happens to the hearts extracted from other people who have transplants. He said didn’t know for sure, but would ask, and hinted that the hearts — those muscular metronomes of life that metaphorically represent our grit and courage — may go nowhere more ceremonial than the trash. (They are safely disposed of, I was assured. And, no, sadly, you aren’t allowed to take your extracted organs home. I asked).

I was lucky to make sure mine wouldn’t fall into a medical black hole and disappear forever, or so I thought.

But now I am not sure. There is a lot of uncertainty at the Mütter right now. I’ve heard many conflicting messages about what will happen with donations, exhibits and online videos, and it looks like the museum is rethinking what its role is in society, according to WHYY’s Alan Yu.

What will happen to my heart is unknown, right now, for sure.

But the very fact that I am writing about this raises an ethically tricky question about how much autonomy we have over our bodies, especially when we receive medical treatment.

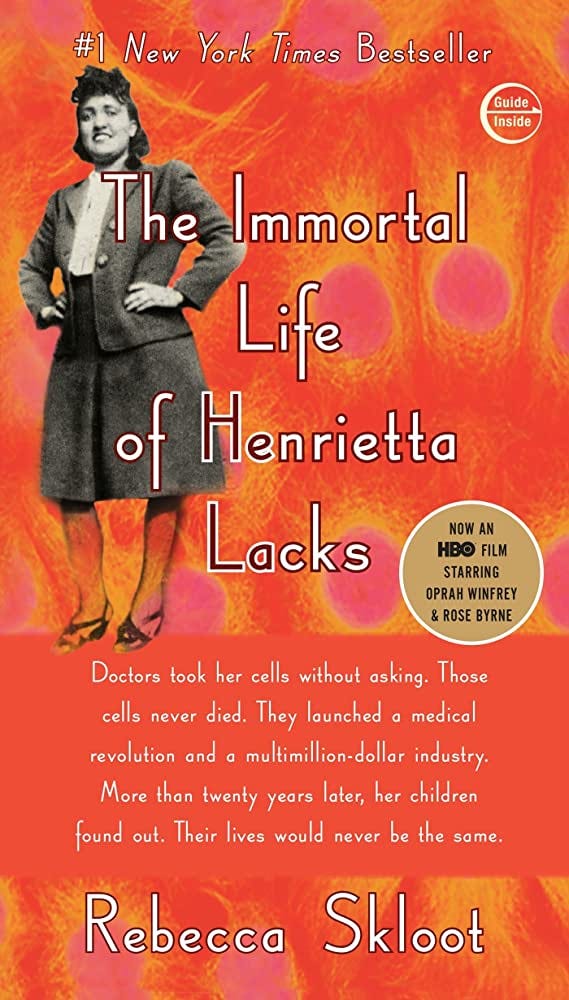

I remember thinking it was odd that I signed away ownership of my heart once a new one was sewn in, but hadn't had a chance to reflect on the idea, until now. I understand there are safety issues to consider but find it disconcerting that something so essential to my being doesn’t belong to me even after it's taken out. It's odd that any bit of you doesn't belong to you after it's removed. (Case and point: Henrietta Lacks.)

My case is nowhere near as severe as hers was. But that thought of who owns us touches on a sticky point of autonomy when we navigate the medical community and reminds me of an even larger question of self. One I have heard arises with invasive treatments such as electrodes implanted in the brain — an up-and-coming treatment for depression.

I knew nothing about this treatment until I started editing a fantastic newsletter series by my colleague Laura Sanders. In her reporting, she directly asked people undergoing deep brain stimulation if they ever felt like the electrodes implanted in their brains or the scientists controlling them were changing who they were in some way — if they felt the computers stimulating their brains were making them into something much different than they were.

The answer was startling. It was a resounding NO.

These people felt like they had more autonomy than ever. I won’t get into the details because Laura’s storytelling is inimitable and you should read her six-part newsletter. You can sign up for it here.

What I will say is that I identify with the people in the story. The fundamental core of who they were was restored with their treatment. A heart transplant was the same for me (h/t to Alan Yu for exploring that too).

I am me, again.

But the fate of a part of me could be in jeopardy. And I wonder: What right do I have to reclaim it, if it will not be used in a way I intended? If not, have we learned anything from the story of Henrietta Lacks?

That said, I hope documenting my thoughts here on my first heart isn’t the end, only the beginning.